The Fellowship-winner of Capa Grand Prize Hungary 2021: Róbert László Bácsi

Róbert László presented his work entitled: Nagorno-Karabakh – Missing Generations on October 21, 2021 at the Capa Center

The Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, where 95 percent of the population consists of Armenians, although was once an ethnically diverse part of the Caucasus, claimed independence from Azerbaijan following the collapse of the USSR, in 1996. It has no international recognition as a sovereign state and de jure is still considered to be a part of Azerbaijan.

To comprehend the state of this area, one must be familiar with its history. Even though its inhabitants had mainly been Armenians for all of its history, under the name “Nagorno- Karabakh Autonomous Oblast” – due to pressure from Stalin – the small country rich in natural resources was made part of Azerbaijan in 1921. In 1991, war broke out between the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijanis, resulting in thirty-five thousand deaths. Azeris lost that war, and Karabakh occupied territories that did not belong to the Nagorno-Karabakh region historically. That guaranteed further conflict. The “four-day war” in 2016, and later the 2020 offensive initiated by Azeri forces against Armenian military positions were the results of unresolved territorial and ethnic tension. Both parties suffered heavy losses in the latter, six-week long conflict. Armenians lost the war, and fearing retribution, over fifty thousand people fled their homes in Nagorno-Karabakh, and sought asylum mainly in Armenia.

Currently, Nagorno-Karabakh is an “island” once again, with a significant part of the territories once belonging to it, just like its borders, being overseen by Azeris. Its only contact with Armenia is through the Lachin corridor, occupied by Russian peacekeepers.

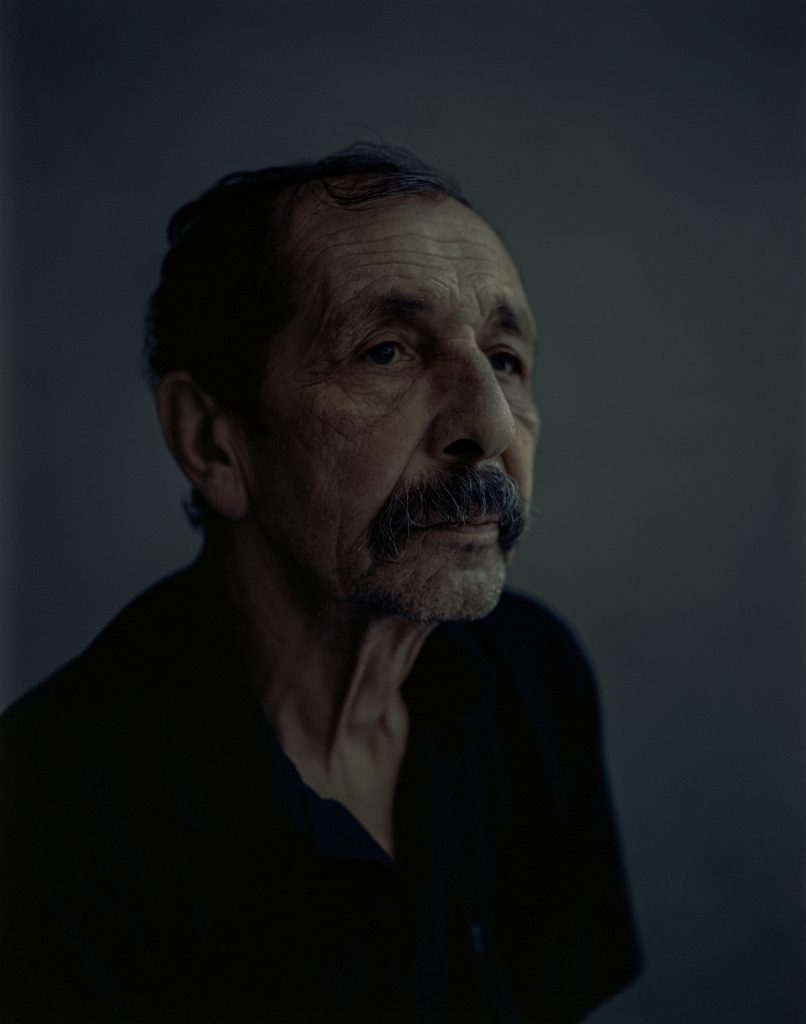

I was immediately touched by the ambivalence in the fates of people living in Nagorno- Karabakh, as well as the emotional state it causes, an experience shared by many residents of post-soviet states. The country announced its independence, but, for several reasons, it was not recognized by more influential and powerful states. Like a boat stranded between two shores on open water, unable to dock and find its destination, people living in Nagorno-Karabakh – as well as others in former territories of the Soviet Union – never experienced true freedom following the downfall of the USSR. Their attempts to form an independent nation-state and to gain a land of their own have mostly led to torturous armed conflicts, which they haven’t been able to end for decades. Getting to know these societies, understanding their circumstances, unwrapping and showing their lives with the toolkit of photography has been a main professional concern for me since 2009. Driven by the desire to share the fate of this small country with the world, I go back from time to time to Nagorno- Karabakh, with the aim to bring their reality and the human fates behind the news closer.

The lives of entire Armenian generations had been determined by the wars. Even the Armenian genocide, which occurred one hundred years ago, has some effects that are present to this day. The generation that should have formed the spine of society in the past decades is almost completely missing. Some of the soldiers who took part in last year’s armed conflicts lost one or both parents during the previous war, while others joined the army alongside their fathers, those veterans of the previous war, who had fought for the independence of their country.

Those fallen in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflicts rest in the Yerablur Military Pantheon, most of the soldiers who died in 2020 only being 18 to 20-year-old young men. Many sons of yet another generation were lost last year, deepening the conflict between Azeri and Armenian people and their respective countries even further. When will this end? The answer is unknown.

In an earlier stage of the work, the artist was a recipient of the József Pécsi Photography Scholarship of the Ministry of Human Capacities.